The Renaissance of the Swiss Watch Industry

A dissertation presented to the Department of Economic History at the London School of Economics.

For Marc Bridge, At Present Founder + CEO and host of The Materialist podcast, jewelry and watches are more than a job, they have been a lifelong passion and intellectual interest. During his graduate studies in Economic History at the London School of Economics, his research examined the forces that shaped the modern Swiss watch industry following the “quartz crisis” of the 1970s and 1980s.

His 2006 dissertation is presented below in its entirety, as referenced on the Acquired episode on Rolex. For full citations, you can download the original at the bottom.

Abstract

The Swiss watch industry during the 1970s and 1980s was a textbook example of a dominant national industry that lost its lead amidst a technological paradigm shift.

Swiss watchmakers had a tradition of atomistic production using skilled labour to produce mechanical watches for a variety of markets. New competition, in the form of quartz movements produced by integrated manufacturers with lower labour costs fundamentally challenged the Swiss industry. From a post-war high of 85 percent, Swiss market share (measured in units) fell to 15 percent in 1980 as a result of this new competition. The Swiss responded by rationalizing production and incorporating the new technology, but more importantly they increasingly sought to de-commoditize their product. By repositioning Swiss watches as more than utilitarian timekeepers, they transformed their offering into a fundamentally different product. Through marketing, Swiss watches became symbols of fun, fashion, beauty, art and provocation that happened to tell the time as well. Rather than being creatively destroyed, the mechanical movement increasingly came to be seen as a luxury product that appealed to affluent consumers seeking an authentic status symbol. Swiss watchmaking recovered from its near extinction in the early 1980s by emphasizing different values and producing different products. While Swiss unit output today constitutes only a tiny fraction of the worldwide supply of watches, in value terms it remains the undisputed king. By changing the nature of competition and increasingly producing more, and more expensive, mechanical timepieces backed by comprehensive marketing efforts, Swiss watchmakers were able to resurrect their business. The “renaissance” of the Swiss watch industry was as much about selling art as science.

Introduction

Can a national industry which lost its competitive advantage and forfeited its market dominance at the hands of a paradigm shift in technology and production technique successfully regain its supremacy? Can it do this by embracing the seemingly antiquated technology?

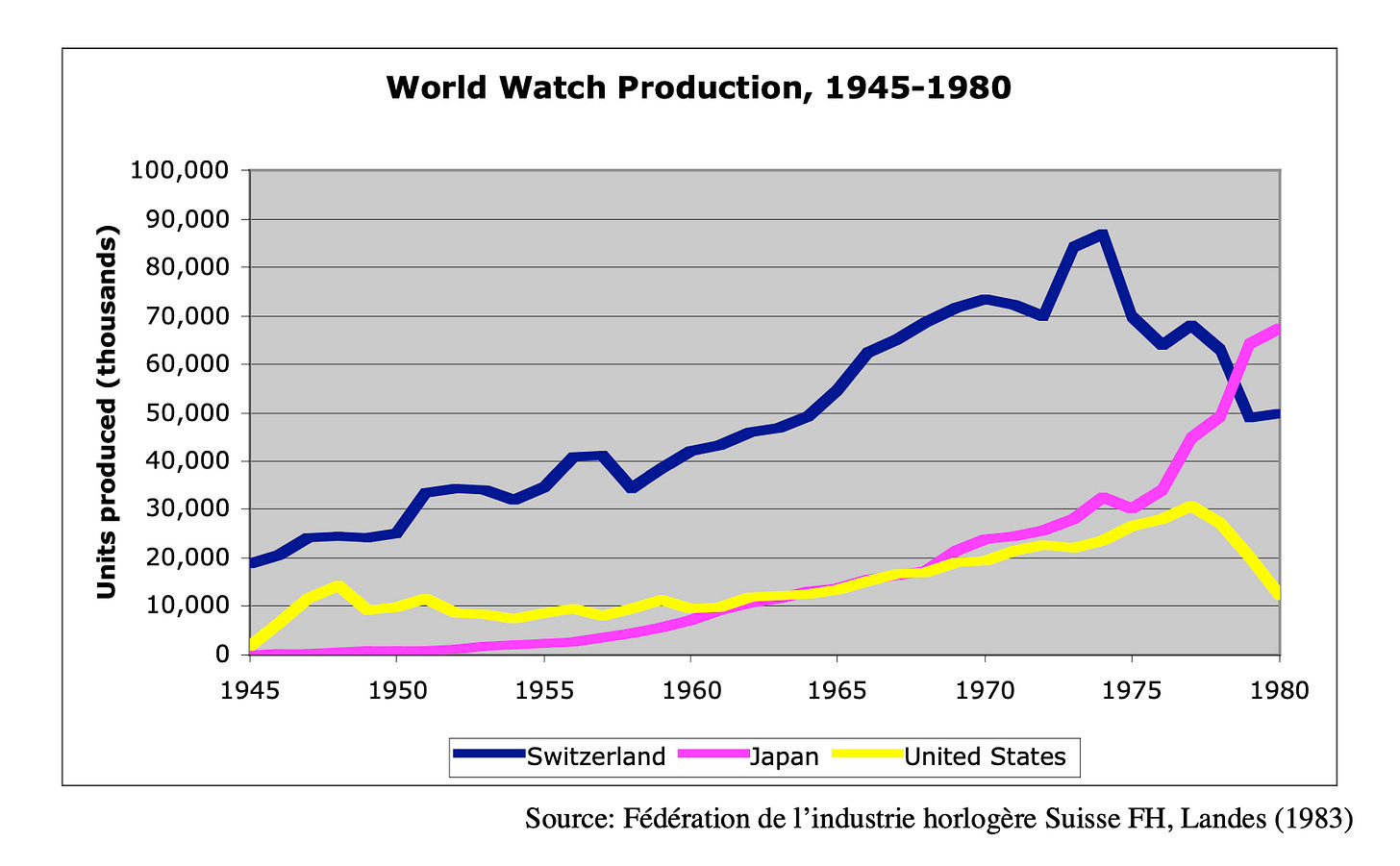

Joseph Schumpeter argued the capitalist economy is propelled by “competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization…competition which…strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives.” 1 In the late 1970s and early 1980s the Swiss watch industry was a textbook case of industrial failure amidst the gales of Creative Destruction and an example of manufacturing migrating abroad from countries with high labour costs to those with much lower costs, particularly in Asia. Swiss entrepreneurs missed opportunities, but the deck seemed stacked against them. Following the Second World War, the Swiss produced more than 85 percent of the watches sold around the world, measured in units. By 1980, they only produced 15 percent of total units. A revolutionary product, the quartz timekeeper, produced in a fundamentally different way by vastly more efficient and integrated manufacturers heralded a paradigm shift in the industry and threatened the long dominant leader. On the quality criteria which watchmaking had always been judged, accuracy, the new product was demonstrably and consistently superior and the techniques used for its manufacture enabled its producers to sell it at a fraction of the cost.

Yet the Swiss industry survived and recovered substantially. Even if it never again produced the majority of the world’s watches, it regained its position as the most important watchmaking region of the world and the largest producer in value terms.

Furthermore, it continued to be one of the largest and most profitable industries in its country and one of its primary exporters. It is a story of entrepreneurial failure as well as success and an investigation of the divergent ways industries (and their home countries) can be successful in a global market.

Why Swiss watches?

It is through the prism of Schumpeter’s Creative Destruction, the perpetual waves of upheaval and renewal that he wrote were the “essential fact about capitalism” and “what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in” that I am best able to conceptualize the dynamism of the modern economy.2 The economic historian N.F.R. Crafts wrote that economic growth “typically involves substantial changes in the structure of the economy and the composition of output,” and that over the last two centuries this “technologically progressive” climb has enabled society to produce goods and services that better satisfy consumer wants.3 In the Schumpeterian rendering the entrepreneur is the catalyst of progress because he introduces the technology and organization efficiency, he is “the powerful lever that in the long run expands output and brings down prices.”4

Yet history seems to illustrate that the supply of entrepreneurs varies over time, as does their quality and effectiveness. Moreover, national differences seem to matter in their abundance and ability to instigate economically advantageous change. David Landes argued that cultural, social and religious factors can inhibit or induce the supply of entrepreneurs, while Alexander Gerschenkron responded that entrepreneurs are an economic factor that respond in tune with changing economic conditions. Their perspectives condition the work of thinkers as diverse as S.N. Broadberry, Bernard Elbaum, William Lazonick and Alfred Chandler who sought to explain comparative economic performance as a product of varying incentive levels for entrepreneurial activity.

Landes wrote that watchmaking is “a marvelous laboratory for the study of the human (entrepreneurial and labour) factor in industrial achievement” because, “clocks and watches can be made anywhere—anywhere, that is, where skilled hands can be guided and supervised by ingenious technicians and creative designers.”5 It is also a useful perspective for exploring the trade-offs between mass- and flexible-production. Due to the nature of its production, historically watchmaking was more dependent on human rather than physical capital. It was an ideal industry for both a mountainous European country and a Asian archipelago with scarce natural resources.

This study will examine the changes that occurred in the Swiss watch industry during the late 1970s and 1980s by first considering the industry’s historical inheritance. As Paul David and others pointed out, path dependency and technological “lock-in” affect the choices and potential costs of adopting new technologies.6 The Swiss response will be explored using contemporary news accounts: how did watchmakers plan to respond and were they indeed successful in implementing their plan? The changing nature of the industry will be analyzed using historical production and export data.

Advertising is examined throughout to illustrate the attributes watchmakers stressed in promoting their products. Finally, interviews with industry leaders help explain the changes and the role of entrepreneurialism in shaping the Swiss watch industry in the last quarter of the 20th century.

History of watchmaking in Switzerland

Since the seventeenth century, Swiss watchmaking has been concentrated in the Jura mountains along the French border. A young man named Daniel JeanRichard (1665- 1741) is given credit for founding the industry amongst the barren soils of a region “singularly propitious to theological contemplation”. 7 JeanRichard adopted the production techniques of watchmakers nearby in Geneva, known as établissage, whereby an établisseur would organize the production of a variety of subcontractors and market the output using his reputation as an effective “brand” for the final product.8 Like similar arrangements in the weaving industry of Lancashire, this putting-out system established a tradition of small-scale, disintegrated production.9

Watch producers in the Jura Valley could specialize to a high degree because of their geographic proximity to one another. Agglomeration made possible a flexible system that could easily respond to changing demand patterns and encouraged innovation, as Landes wrote, “whatever you wanted, someone somewhere could make. No run was too small, no order too special.”10 Fixed costs were low and the risks to entrepreneurs were accordingly minimal. Proximity benefited his productivity, as Alfred Marshall wrote, “great are the advantages which individuals following the same skilled trades get from near neighbourhood to one another…The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are, as it were, in the air.”11 They also created an extensive system of apprenticeships and training programs.12 Geographic concentration reduced the transaction and information costs associated with market organization and made the invisible hand an efficient basis of organization. Firms remained small in scale and labour was often supplied by the family. In a labour-intensive industry, neither technological nor organizational innovation substantially increased the minimum efficient size of the firm.

Amy Glasmeier suggested the global watchmaking industry evolved through five distinct stages, beginning with craft production, followed by putting out, protofactory assembly, mass production, and evolving into vertical integration by the second half of the 20th century.13 Such over-arching categorizations minimize the historical residual of an ongoing craft tradition in watch-making. While one can find historical examples of mass production techniques dating back to the middle of the 18th century when a man named Frédéric Japy employed a variety of machines to mass produce a basic ébauche (the blank that is the foundation of the watch movement), the craft tradition remained an integral part of watchmaking well into the 20th century. François Jequier claimed a central characteristic of Swiss watchmaking was that “the appearance of new manufacturing processes did not eliminate old practices, and usually the two systems operated side by side, which explains the extraordinary heterogeneity of this sector, first as a craft and then as an industry.”14

Rothbarth and Habbakuk famously argued the employment of capital-intensive production techniques was the product of supply-side conditions, namely the scarcity of skilled labour and natural resources. This is often forwarded to explain why European technology remained so relatively skill abundant as America embraced capital-intensive mass-production techniques in the late nineteenth century. S.N. Broadberry emphasized the demand side of the equation as well.15 Swiss watch production continued to produce a variety of goods for a heterogeneous market. Swiss watchmakers were adept marketers since they began producing for export markets in the eighteenth century. They realized American buyers used the number of jewels in a watch (rubies used as bearings for pivoting components) as a proxy for quality, and produced watches with high numbers of jewels, even as this was uncorrelated with actual quality. The plethora of Swiss watchmakers produced for every segment of the market, as Landes wrote, “The Swiss, as always, made and sold the worst and the best; they sold what the market wanted.”16

Contrary to the American experience described by Alfred Chandler, the move to factory production in Europe was not notable for the elimination of skilled workers.17 William Lazonick argued to the contrary that the production of “high quality products at low unit costs” required an “ample supply of highly skilled and well-disciplined labor.”18 Factory production in the Swiss watch industry remained disintegrated to a large degree, following the trajectory of early manufacturing work done at home under the putting-out system. Home work continued to be a major component of the Swiss watch industry into the second half of the 20th century. In 1970, nearly 15 percent of labourers in the Swiss watch industry (13,403 of 89,448 total employees) were self-employed and classified as “home workers”.19

The industry saw moments of concentration, rationalization of production and entrepreneurial initiative, particularly when the industry faced competitive threats. By the late 1870s, American manufacturers were producing and marketing watches made with precision machine tools in large plants employing hundreds of workers. Despite some resistance, leading Swiss établisseurs responded by building larger factories equipped with state-of-the-art technology. Following the American challenge, the proportion of home-workers fell from three-quarters in 1870 to less than one-quarter in 1905.20 Jequier reasserted that the development of plants and factories did not destroy the établissage, which utilized its flexibility to take rapid advantage of market opportunities afforded by changing fashions.21

The depression of 1929 struck an industry that exported 98 percent of its production and caused exports to fall from a total of 307 million francs (20.8 million units) in 1929 to 86 million francs (8.2 million units) in 1932.22 The Swiss government responded by creating the holding company, ASUAG, the Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindsutrie AG (General Corporation of Swiss Horological Industries) in 1931 and passing a federal statute in 1934 that gave the watch producer’s cartel agreement the force of law in dividing output and restricting trade entry.

However, even the firms consolidated into ASUAG continued operating as effectively autonomous groups. The industry remained composed of mostly atomistic producers, though they thrived following World War II as demand rebounded and internal and external competition was limited. With the cartel agreement in effect and the industrial capacities of Japan, Germany, France, and the Soviet Union effectively crippled, Swiss watchmakers recorded record profitability. The industry’s share of world production peaked, briefly surpassing 85 percent when they manufactured 18,800,000 of the world’s total production of 21,567,000 watches in 1945.23 This total was produced by nearly 2,500 individual companies, 90 percent of which employed fewer than 50 people.24 Even after two centuries of process improvements and increasing mechanization, production costs of a watch were still dominated by labour costs, which accounted for 60 percent of the cost of the product. Swiss watch production employed more than 80,000 people and accounted for 10 percent of Swiss GNP and 20 percent of exports.25

Post-war competition

It was unreasonable to expect the Swiss to have maintained such a preponderance of market share as the economies decimated by war put themselves back together.

Nevertheless, the Swiss continued to control more than 40 percent of the global production of watches (measured in units) until the 1970s, a level similar to their long term trend.

Jequier argued post-war success and legalized cartelization bred self-satisfaction amongst watchmakers and “stifled initiative and innovation.”26 Within Baumol’s model of entrepreneurship, societal incentive structures dis-incentivized productive innovation and promoted unproductive rent-seeking. Changes “in the economy’s structure of payoffs” affect aggregate performance, he claimed. 27 A series of technological and market developments during the middle decades of the 20th century began to shift the competitive balance in the watchmaking industry. American companies, particularly Waltham and Elgin, competed against Swiss watches beginning in the latter part of the nineteenth century by harnessing the kind of mass production techniques described by Chandler, including the three-pronged investment in manufacturing, management and marketing. American watch manufacturers averaged 529 employees per firm in 1900 (Swiss firms averaged closer to 20).28 Turn of the century American “dollar watches” were the first to be manufactured with interchangeable parts using specialized production machines. While none of these were as precise as hand-made Swiss watches, they opened new markets for watchmaking.

In the years following World War II, the Swiss faced increasingly strong competition in the low-end of the market from a new American entrant, Timex. A relatively unsophisticated, unjeweled, clock-type watch with a pin-lever escapement that sold for $6.95 and $7.95 (and didn’t keep particularly accurate time), the Timex was a utilitarian offering and a successful one at that. Bypassing traditional distribution channels like jewelry stores, Timexes were sold in drug stores, supermarkets, and hardware stores.29 Landes claimed “Timex represented the culmination of two centuries of striving: parts were standardized and made interchangeable not only within plants but among plants; and machines were automated as much as possible so as to reduce the human element to a minimum.”30 In 1960, eight million Timexes were manufactured and by 1973 it controlled 45 percent of the American market and 86 percent of domestic watch production, supported by a vigorous advertising campaign.31 Technologically, the Timex was not a radical departure from its predecessors, rather it was a triumph of manufacturing and marketing efficiency, “the extreme expression of older developments.”32 It was what Chris Freeman and Carlota Perez classify as an “incremental innovation” in their taxonomy of innovations. It was the type of continuous invention that occurs “not so much as the result of any deliberate research and development activity, but as the outcome of inventions and improvements suggested by engineers and others directly engaged in the production process.” 33

The next step in the evolution of the industry was the introduction of the tuning- fork watch by the American company Bulova in 1960. Developed in a Swiss lab by Max Hetzel, a Swiss engineer, and offered to disinterested Swiss watch manufacturers first, the Accutron claimed vastly superior accuracy. Bulova advertised the Accutron would be accurate within 2 seconds a day or a minute a month, a veritable shot across the bow of the Swiss industry whose marketing had always stressed that the quality of a watch should be judged on its accuracy. The best Swiss mechanical watches (what today would qualify as “Chronometers” by the Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres) have average variations in rate of between –4/+6 seconds per day.34 The Swiss were embarrassingly forced to license tuning fork technology to use in their own watches.

While a harbinger of the technological dislocation to come, the tuning fork in and of itself was not a massive technological discontinuity. Glasmeier argued in fact “the technological trajectory of this intermediate technology was actually complementary with mechanical watch technology.”35 While its mechanism for time keeping was unique, manufacturing it required the high levels of skill and technical competency the Swiss had in abundance. The tuning fork was a “radical innovation”, the second level of innovation in Freeman and Perez’s taxonomy, but not one that should have necessarily altered the global competitive balance.36

Paradigm shifts and industrial disruption

The technology that did herald a “techno-economic paradigm” shift in the watchmaking industry was yet another product of Swiss research labs. The Centre Electronique Horloger (CEH) in Neuchâtel was established after the embarrassing tuning fork debacle in order to create a better time keeping mechanism. By 1967, their new quartz chronometers were twice as accurate as the best mechanical timepieces ever created and improving rapidly. Mechanical watches relied on centuries old technology that measured the passage of time by releasing energy from a wound spring through a series of gears (called the wheel train), regulated by a mechanism called an escapement.

While conceptually simple, this task required more than a hundred moving pieces built to microscopic tolerances and designed to perform under variable conditions (temperature, position) as well as continuous friction and stress for many years.

That so much complicated micromechanical activity occurred within such a small space helps explain why the industry relied on talented craftsmen for so long. While process and product improvements were continuous (notably the miniaturization required to supply the growing demand for wrist watches in the early 20th century), the underlying technology remained the product of the mechanical era of the eighteenth century.

Quartz technology, by contrast, is underlined by its microelectronic foundations.

It exemplified the new “techno-economic paradigm” powered by the exponentially expanding capabilities of semiconductor chips.37 The technology was based on the discovery of the phenomenon known as piezoelectricity by the French physicist Pierre Curie in 1880. Curie determined that quartz crystals vibrate mechanically when external voltage is applied. This vibration was stable and could be divided into a constant frequency for time-keeping purposes. Theoretically, all a pendulum, or its cousin the wound mainspring, provided was a constant beat from which the flow of time could be regulated. The quartz crystal offered that at a much higher rate without suffering the adverse effects of temperature, position, or atmospheric pressure that compromised the accuracy of mechanical timekeepers.

The challenge was to incorporate quartz timekeeping technology (which had been a feature of observatory clocks since Greenwich in 1939) into a package small enough to fit on the wrist.38 The rapid vibrations of the quartz crystal needed to be counted and transformed into a useable impulse for telling time. The growth in capacity and miniaturization of electronic circuits made this possible, as the capacity of integrated circuits grew exponentially.

Battery-powered, quartz regulated watches reliant on integrated circuits were a fundamental discontinuity in the evolution of watchmaking. The technology and the techniques necessary for producing the new products were vastly different than anything that came before. In Landes’s words, “science had defeated art.”39 Centuries of accumulated skill and human capital around the old forms of production in watchmaking were worth little in producing the new commodity. This need not have spelled disaster for the Swiss industry, however, as they were not lacking in science. A constellation of research labs, including the CEH, were working on new microelectronic technologies and were collaborating with leading edge companies in other countries to integrate new technology into watches. The only thing missing was the dynamic entrepreneurship, “the manufacturers of watches were not interested. Those years of comfortable, sheltered monopoly rents had cost the industry what had once been its more precious characteristic—its Neuerungsfreudigkeit, its joy in innovation.”40

Landes wrote at length elsewhere about the effects of cultural conservatism and entrepreneurial failure in explaining relative economic decline, particularly in the case of Britain and France, and a similar strand runs through his work on the watch industry.41 The problem with cultural conservatism as a factor dictating entrepreneurialism is that at times it is a positive and at other times a negative quality. Small, family run firms contributed to the dynamism and flexibility of the watch industry in its first two centuries, but then became a liability in the face of certain new competition. His description of the Swiss manufacturer content to gather the “monopoly rent” is reminiscent of his dismissal of the French entrepreneur who was perfectly happy to reap his “entrepreneurial profit” but not undertake the task of expansion which required exertion and possibly bank finance.42

Different times call for different measures

Curiously for a historian of technological change, Landes’s entrepreneurial model does not recognize that adapting to paradigm shifts requires a different kind of entrepreneurialism. Market structures and production techniques necessary for success change over time, a process catalyzed by changing technology. Production techniques, however, are subject to path dependency. Broadberry argued that the differences in technological approach and productivity over time between the United States and Europe were due to the tendency of factor accumulation to take place around techniques specific to their particular method of production. Furthermore, the most successful industries had the greatest degree of accumulation. This is what Clayton Christiansen called “the innovator’s dilemma.” 43 Success made changing course difficult.

The sort of entrepreneurial skill, the “joy in innovation” Landes attributed much of the Swiss success to in facing earlier competitive threats is a different kind of skill than facing a paradigm shift. Christiansen argued companies (and industries) face two new types of technology: sustaining technologies and disruptive technologies.44 Sustaining technologies, “improve the performance of established products, along the dimensions of performance that mainstream customers in major markets have historically valued.”45 Disruptive technologies, by contrast, offer a different value proposition and herald “a change in the basis of competition.”46

It is difficult for successful companies to take advantage of disruptive technologies. Their success is the very product of understanding how to meet the needs of customers within the old paradigm. When facing a disruptive technology, the rules of competition change fundamentally. Christiansen’s study is a business theory parallel of Donald McCloskey’s work on the relative decline of Britain. Businesses behave rationally in facing prevailing economic constraints. The challenge in both situations is to reorder the prevailing constraints so they are more in line with new threats. This is neither an easy nor a costless transition. Broadberry argued, “large technological shifts or market change can cause problems because of the specific skills needed to reap the economies of scale and scope in any particular technique. Such changes can undermine the value of specific human capital, which can cause serious adjustment problems.”47

Part of the problem is that disruptive technologies “bring to a market a very different value proposition than had been available previously.”48 That was certainly the case with quartz watches. Micromechanical know-how meant little, barriers to entry were lowered as basic quartz technology was in the public domain (unlike the tuning-fork), and the economies of scale necessary for efficient production of the new technology increased drastically. The transition fits within the Nelson and Wright model of a move from an empirically-based technology that relied on tacit knowledge and learning by doing to a more scientifically-based technology that required specialist scientists and engineers.49

No matter how many generations one’s family was involved in watchmaking, without advanced training in electrical engineering it was nearly impossible to calibrate a stepping motor and integrated circuit. The result was something that “still looked like a watch but was in reality a different product.”50

One of the first groups to enter the new fray lacked any historical connection to watchmaking and was all “science” and no “art”. Seeking a downstream market for their newly developed semiconductors, American manufacturers like Texas Instruments, Intel, National Semiconductor and Hughes entered the industry, investing heavily in machinery to produce massive quantities of inexpensive watches that displayed the time digitally. While these large industrial firms possessed impressive manufacturing knowledge, strong financial capacity, and made massive capital investment in production equipment, they lacked the skill to pick the right products for the market. Their products featured light emitting diode (LED) displays when the market preferred the liquid crystal displays (LCD) that didn’t require the operator to push a button to read the time. They failed to effectively promote their wares and fell into a destructive pricing war that led to their ignominious exit from the business less than a decade after their entry.51

The stronger challenge came from Japan. While not new to the watchmaking industry, Landes argued it was easier for Japanese firms than Swiss companies to harness the new innovation “because it was derived from the existing base of knowledge and was thus neither earth-shattering nor culturally displacing.”52 Unburdened by the legacy of craft-based watch production, it had produced mechanical watches but by mass production techniques, Japanese producers could more easily adopt their mass production lines to the new technology. Unlike the Swiss, Japanese industry developed its nascent scientific capabilities thanks in large part to support from the Japanese government and technological advances in microelectronics made during World War II. Japanese manufacturers had developed strong technological competencies in producing electronic devices and integrated circuits already.53

The leader was privately-held Hattori Seiko, one of the first watch companies to adopt a vertically integrated manufacturing process, a striking change from the Swiss technique. Seiko adopted assembly-line production techniques after visiting American automobile plants. It had integrated facilities for producing most watch components and maintained “tapered” vertical integration for components it did not produce entirely in house. Everything was manufactured in plants grouped closely around Seiko’s two primary assembly plants. Such integration (and the lower cost of labour) afforded them a 15-40 percent variable cost advantage over the Swiss in producing mechanical watches during the 1960s. 54

Seiko invested heavily in research and development and its production was based on standardized parts, automated production and massive throughput. An executive with one of Seiko’s Japanese competitors Citizen commented, “handicraft is nothing in the quartz age,” and Seiko’s production reflected that sentiment.55 New production lines were designed to produce from 100,000 to more than 1,000,000 watches per year utilizing robots and new automated techniques. Seiko hoped to build plants that could build watches without direct labour, except for inspection and quality control functions.56

Rather than competing with the dueling American semiconductor manufacturers in their ill-conceived bid to capture the low-end digital watch market, Seiko introduced a broad line of watches that displayed the time in traditional analog format, even as it was powered by electronic quartz movements.57 The 2 million watches Seiko sold in the United States in 1977 were supported by $10 million in advertising, mostly on television.58 As a British-based watch importer commented, “Seiko is very good at marketing and the Swiss aren’t.”59

Before entering the United States officially in 1970, Seiko cultivated its image with American servicemen serving in Asia during the Vietnam War. After buying inexpensive and reliable Seikos in military PXs, veterans came home brand ambassadors.60 By focusing on the mid-priced quartz watch sector of the market (US$65- US$350), Seiko experienced 16 percent average annual growth from 1968 to 1978 and recorded over US$1 billion in worldwide sales, more than double the second largest producer, ASUAG.61 By the early 1980s, Seiko’s advertising slogan, “Someday all watches will be made this way,” seemed prescient.

Storm clouds all around

By the middle of the 1970s, Swiss watchmakers were confronted with an unenviable industrial position: strong and dynamic foreign competitors were attacking not just the margins of their once dominant position but striking its very core with superior technology produced at a fraction of the cost. Freeman and Perez defined their paradigm change as “a radical transformation of the prevailing engineering and managerial common sense for best productivity and most profitable practice”62 It is noteworthy that new products became available, but the more striking shift was in the cost structure of their production. If path dependency and technological lock-in make playing catch-up by adopting new techniques difficult, differing factor conditions can render it nearly impossible. Broadberry suggested that while “macro-inventions” might provide an escape from path dependency and a jettisoning of antiquated techniques, a country’s factor conditions may alter the costs of using new technology so that their employment is still not efficient.63 Finding the proper competitive balance in adopting new technology for a specific market is an entrepreneur’s job, but entrepreneurs were scarce in the decaying Swiss industry during the 1970s.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the 1970s were not an ideal time for a nation to be facing a drastic shift in its technological position. The oil crisis in the early part of the decade led to the revaluation of the Swiss franc as an influx of so-called “petrodollars” fled massive inflation abroad.64 Glasmeier commented, “what was good for the Swiss banks was devastating for Swiss manufacturing industries, particularly in export sectors like watches.”65 The franc rose from 23 cents under the fixed exchange rate to 46 cents in 1980, with fluctuations as high as 70 cents during the decade.66 The changing macroeconomic climate advantaged Japan, whose undervalued currency made its output, already produced more efficiently than their Swiss counterparts, “seem like it was on sale.”67 A policy of tariff protection for nascent Japanese industries further distorted the trade picture.

Further pressure came from watch assemblers in Hong Kong who jumped into the low-end of the market producing low-cost digitals by utilizing intensive and relatively inexpensive labour. The success of Hong Kong manufacturers illustrated the new economics of watch production. In the electronics era, “there would never be a period of time when price declines moderated.”68 Economies of scale became a requisite for watch production, arguably even at the top end. Mass throughput was necessary to assure quantity and quality of components and consistent price levels.

For a time, Swiss manufacturers consoled themselves that the quartz “craze” was a passing fad. A confidential memo prepared by the Federation Horlogere sought to reassure watchmakers that in 1970 “98 percent of sales still consisted of mechanical timepieces, and that the electronic, solid-state timekeeper, though accurate, did not constitute a sufficient advance to sweep the market.” Indeed even Japanese unit output was less than 6 percent quartz in 1974.69 Pitched to the early adopters who bought on the basis of novelty, the first quartz watches cost thousands of dollars and were not very reliable. Swiss watchmakers assumed competition would continue as it always had, adding features or shrinking size gradually would earn them a premium. Characteristic of a paradigm shift, however, the new technology started from a position of initial disadvantage but caught up rapidly, and gained significant market share commensurately. Whereas quartz output only accounted for 3 percent of the units produced in 1975, by 1979 31 percent of new watches were quartz-powered.70 According to veteran watch journalist Joe Thompson, quartz watches were seen as “new, exciting, ultra-accurate, ultra-reliable, agents of innovation,” and they swept the market.71

Disruptive technologies have rapidly falling learning curves as firms learn how to maximize the advantages of the new technology. When technologies are new, the avenues for their improvement are comparatively wide open. Prices fell, demand grew, and production expanded dramatically. By the end of the 1970s, engineers had solved many of the problems limiting the mass appeal of quartz watches. Power consumption was reduced, battery life extended five-fold, cases made thinner and narrower, and features like calendars, chronographs and alarms added. Most importantly, prices fell to a level around 2-3 percent of what they had been at the start of the decade.72 The Swiss collaboratively produced a variety of quartz products including the Beta 21 introduced in 1970, but their electronic efforts were an afterthought. Limited by their legacy production system and labour costs that seemed to make production prohibitively expensive, the Swiss saw a limited future for the quartz watch and subsequently forfeited the low-end of the market to Hong Kong and Japanese manufacturers in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Facing the prevailing marketing environment of the time in light of relative factor costs, this was a rational decision, just as McCloskey claimed the actions of British entrepreneurs were rational in a neoclassical paradigm. The Swiss would stick to the upscale markets where they maintained an advantage. The problem with moving upward in the face of new, particularly technological, challenges is there is no economic reason why the more efficient competitors who capture the low end cannot transfer their skills to higher end products. The decline of the craft-based British clock and watch industry in the 19th century when faced with cheaper Swiss competition suggests there is no iron-wall between luxury and mass-market products, especially when the producer under threat responds by pleading for government support and protection (and outlawing the use of new technology, as British manufacturers successfully lobbied Parliament to do). The technology that debuts on a Mercedes generally finds its way into a Hyundai—over time that process occurs more rapidly. The only choice is for the upscale producer to continue innovating to stay ahead of the curve. The British did not, would the Swiss learn from history?

Things fall apart

The beginning of the 1980s was a depressing time for the Swiss watch industry. In 1979 the Japanese announced for the first time that they produced more watches than the Swiss.73 Even as worldwide demand for watches grew, Swiss production fell. In 1980 Swiss production shrank to about 50 million units, a level similar to its 1965 output, from a high of 87 million six years earlier.74 Challenged by new technology, lower cost and more efficient competitors and a disadvantageous macroeconomic climate, the industry atrophied. Without the necessary demand to sustain the scale of industry that had developed, the number of firms fell from more than 2,000 in 1960 to less than 500 in 1980, and the workforce fell from more than 90,000 to 46,998 over the same time in a combination of consolidations and bankruptcies.75 Consolidation was rightly seen as necessary to make the large investment in research and development required to compete with integrated producers like Seiko, but the consolidated firms faced their own hardships.

The industry’s two largest firms ASUAG and SSIH, owner of brands like Omega and Tissot, were responsible for two-thirds of industry sales. While they moved beyond decentralized holding companies in the hope of consolidating R&D and production, Business Week argued in 1981 they went too far in producing a “cumbersome central staff that lacks the flexibility to cope quickly with problems or grasp market opportunities.”76 The inefficiencies of scale offered by the invisible hand gave way to the bureaucratic gridlock of the Chandlerian firm. SSIH lost $81 million in 1979 and depleted its entire capital base, which led a coalition of Swiss banks to offer a $150 million emergency loan package. Soon thereafter, ASUAG’s own finances reached the brink and the Swiss federal government and largest banks took control of the two companies, seeing it as their patriotic duty to ensure the flagship Swiss watch industry did not collapse completely. In 1982 the New York Times reported, “While the days of glory admittedly are gone, the industry and banks are struggling to stake out a clear, if decidedly modest new role for the watchmaking trade.”77 Although ASUAG and SSIH attracted the attention of the government and bankers because of their size, the thousands of small, atomistic producers that were the backbone of the industry for centuries were hardest hit by the changing market. The halving of the workforce disproportionately affected the independent family firms which for generations had produced cases and assembled bracelets for the largest watch houses in the craft-tradition of the établissage.78

In studying their options, the Swiss banks hired a management consultant named Nicolas Hayek to evaluate prospects for the industry. Many analysts suggested the banks sell the still valuable brand names like Omega, Tissot, Rado and Longines to Japanese manufacturers flush with cash and confidence. Hayek would have nothing of it: “when the Japanese took over something, it was dead for the United States and Europe. It was video, television, radio, all these things. And I didn’t accept this view.”79 Hayek argued there was great human and intellectual capital latent in the hundreds of small factories in the Jura. The real value of the Swiss watch industry was the know-how and production capacity, but maintaining this scale of manufacturing was unsustainable as the low-end and increasingly the middle-end of the market migrated abroad.

Hayek’s study of the industry illustrated what he called the “wedding cake” structure of the worldwide market in the early 1980s. In the entry-level (up to $75), global production was 450 million units and the Swiss share was effectively zero. At the middle-level ($75-400), the Swiss produced 3 percent of the 42 million units. Their strength remained in the high-end of the market ($400 and up), where they produced 97 percent of the total of 8 million watches.80 To “save” Swiss production capacity, which he argued was essential to the continued production of the profit-making high-end, stabilize the industry, and save jobs, Hayek argued the Swiss needed to get back into the business of producing watches for every segment of the market. To that end, he proposed merging ASUAG and SSIH to combine the manufacturing power of the former (whose ETA division supplied much of the industry with movements) with the valuable brand names and established distribution channels of the later in an arrangement that would bring it closer to the vertical structure of Japanese manufacturing. He also proposed that the company needed to develop a low-cost, high-tech line of fashionable watches to regain its share of the low-end market and assure demand for millions of watch components. This was the catalyst for the introduction of the wildly successful Swatch.

Building Swatch: saving the industry?

Swatch was such a phenomenal success it is often credited with saving the Swiss watch industry. As the industry started to show signs of recovery by the mid-1980s, the Economist could declare in 1986: “Times have changed—and much more quickly than most people in the industry had dared hope. The reason is the Swatch.”81 Swatch so perfectly exemplified the turn around in the industry and became such a potent symbol of industrial resurgence because it defied conventional wisdom. A moribund industry in a conservative country with high labour costs and a tradition of quality craftsmanship reinvented itself by producing high-style low-cost standardized products in massive quantities using state of the art technology and promoted through provocative marketing. Such a striking apparent about-face is an intriguing prima facie prescription for confronting paradigm shifts and is unsurprisingly the stuff of which a great many business school case studies are written. While a dynamic tale, the underlying economics of the industry show a more subtle transformation than the accepted PR story offers.

Swatch debuted in 1983, the year the banks heeded Hayek’s suggestion and merged the companies. Over the following two years, Hayek consolidated his position and gained control over the merged entity, the Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking (SMH). He argued, convincingly, that he was allowed to take the “blasphemous” step of producing a low-cost, high-volume plastic watch because the industry was so desperate: “if the watch industry of Switzerland at the bottom line made one dollar of profit I would never had a chance to renew it, never. They would have thrown me out and said what do you know about watches you stupid guy, its none of your business. You were not born a watchmaker.”82 He was, however, an entrepreneur, and that was exactly what the Swiss needed to break through the institutional inertia and solve the “innovator’s dilemma”.

The Swatch approach served as the guide for resurrecting the entire industry. The challenge was to leverage the benefits of Swiss production while minimizing the costs. He said, “if we can design a manufacturing process in which direct labour accounts for less than 10 percent of total costs, there is nothing to stop us from building a product in Switzerland, the most expensive country in the world.”83 Hayek stressed the importance of building (not just designing) the product in Switzerland encouraging the domestic market to be competitive, in line with Michael Porter’s prescriptions in The Competitive Advantage of Nations.84 Rather than simply exporting manufacturing to low wage countries, as many encouraged the Swiss to do, the challenge was to make the production process more efficient and find other ways to “add value,” what Edward de Bono called “creating value monopolies” as a way of superceding competition.85

If much of the rationalization of production was a catch-up effort harnessing the technological improvements made by Japanese producers, the more important step was the de-commoditization of the product by promoting the cherished “Swiss Made” label and offering an “emotional” and stylish product. For Swatch this was achieved by embracing colours, shapes and moods that made Swatch a qualitatively different product than anything offered by competitors. Swatch made watches fun. Telling time ceased to be the primary function of a watch. The Swatch was about self-expression, style and beauty. Product life cycles were short and new watches were introduced to match the season. This was the value-added function Hayek believed was his competitive advantage: “we were convinced that if each of us could add our fantasy and culture to an emotional product, we could beat anybody. Emotions are something that nobody can copy.”86

Despite his hyperbole, there is no reason to believe the Swiss have a monopoly on the kind of emotions that resonate with consumers. Had the Japanese offered a similarly stylish low-cost product first, Swatch would not have been credited with saving the Swiss watch industry, even though a similar recovery very well might have taken place.

Swatch helped, but the money was elsewhere

Swatch helped reawaken a slumbering giant by removing the taint of failure from the backs of Swiss watchmakers, helping speed the rationalization and integration of production, and reinforcing the importance of strong brand marketing. Although it contributed 70-80 percent of SMH company profits during the mid-1980s, it was because other brands, most importantly Omega, were heavily depressed.87 Although it sold more than 300 million watches, Swatch was an aberration. No other entry-level Swiss product came close to matching its success.

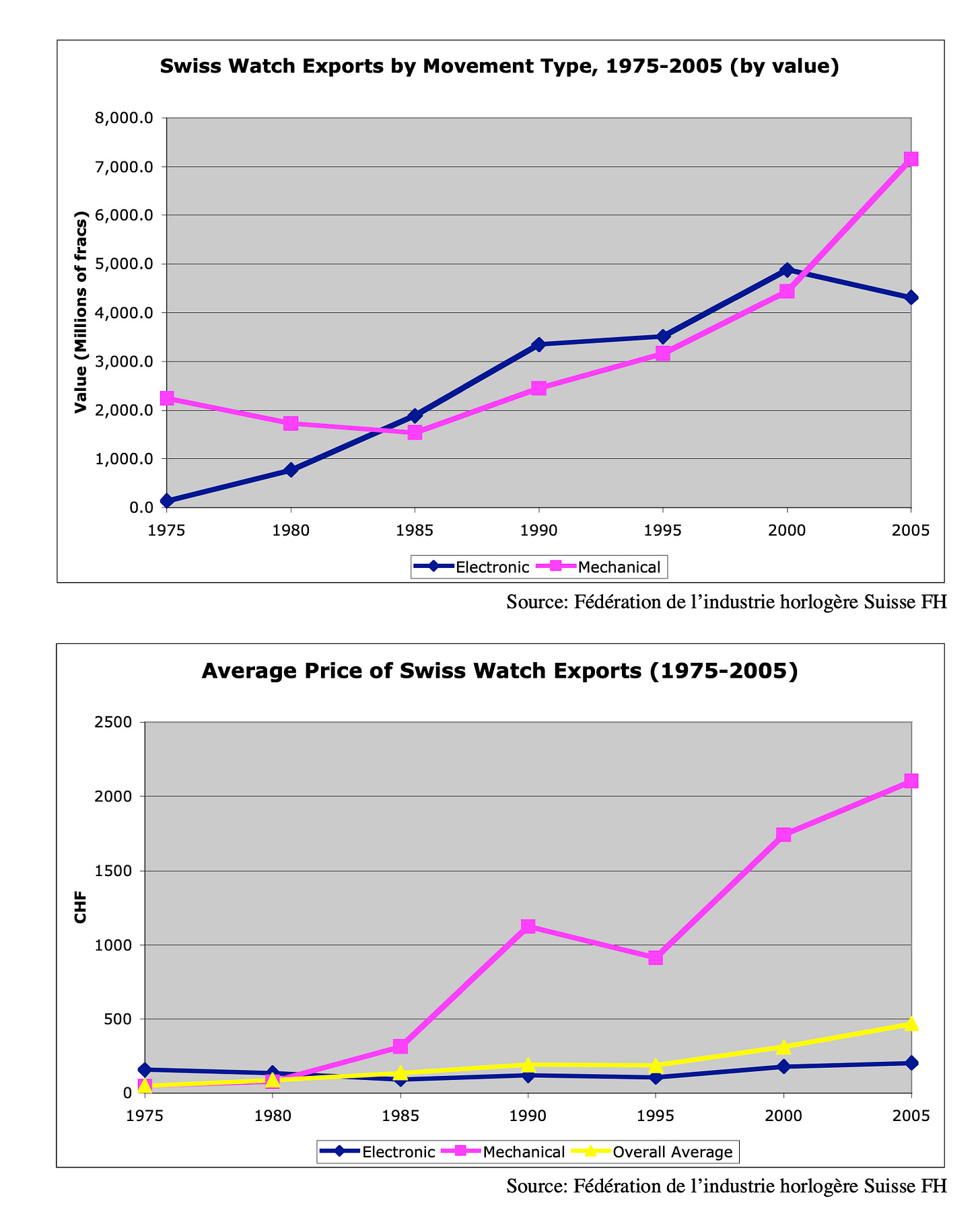

Before the turmoil of the mid-1970s, Omega was the leading Swiss brand and enjoyed greater market share and prestige than Rolex.88 It lost its cachet and diminished its brand equity by introducing too many models at too many price points. In reorganizing Omega to produce fewer and more consistent styles more in tune with the shifting technological paradigm, SMH made a strident effort to put quartz movements in as many Omegas as possible, trumpeted by an advertising campaign that declared: “Today Omega confirms that the electric watch is here to stay.”89 Even as it trailed Japanese and Hong Kong manufacturers in quartz output, Swiss watch production in unit terms did shift from predominantly mechanical to electronic between 1980 and 1985.

Quartz became the dominant technology, and Switzerland was forced to play catch-up to realign its production accordingly. Swiss quartz movements surpassed mechanicals in unit production and contributed more to revenue as well. While quartz watches contributed more to value for the next decade and half, the gap was nowhere near as large as when measured in unit volume. Although the number of mechanical watches produced fell precipitously, the average price of those that were still made grew significantly. The average mechanical watch produced in 1975 cost about CHF 48.50. By 2005 its export cost had grown to over CHF 2100.90 The cost of electronic watches, by contrast, at first fell and then grew so that the export price in 2005 was not drastically different in nominal terms than the 1975 price.

Fearing the technological displacement occurring on the low-end would spread into their highly profitable niche, high-end manufacturers hedged their bets. Rolex, for example, designed and produced a very high quality quartz mechanism it called the Oysterquartz (Rolex’s iconic primary product line is called the Oyster). Introduced in 1977, it was built to the robust standards that marked the company’s mechanical movements, one commentator even claimed it “introduced a new level of craftsmanship to quartz modules, obviously intended to maximize longevity and serviceability, with workmanship apparently superior to that of its best mechanical movements.”91 Incorporating leading edge-technologies to offer greater accuracy and longer life, by for example using electronic compensators for changes in temperature, the Oysterquartz “pushed the science of timekeeping forward” but was a commercial dud.92

The value of marginal gains in accuracy diminished considerably. The basis of competition changed. Improving the movement’s accuracy by a factor of two or more no longer guaranteed market attention. A typical quartz was accurate to within three to four seconds a month (about the acceptable daily deviation for a quality mechanical). So- called “third generation” quartzes, of which the Oysterquartz and high-end products like the Grand Seiko were examples, offered accuracy to within 10 seconds a year, three times the accuracy of basic quartz movement and a striking 100 times more accurate than a mechanical movement. Nonetheless, it was estimated that of the more than 600,000 Rolexes made annually during the 1980s and 1990s, fewer than 1,000 were Oysterquartzes and the line was discontinued in the early 2000s.

Finding the sweet-spot: the watch market post-1980

Despite the phenomenal success of Swatch, the Swiss continued to see the migration of the low and middle end of the market to Hong Kong and China. Quartz, which had been seen as cutting edge technology, increasingly became associated with cheap commoditization. Hong Kong and China together produced more than a billion watches by the first years of the twenty-first century, dwarfing the output of Switzerland and Japan. The average export price of their products, however, was vastly lower: Chinese watches cost an average of $1 and Hong Kong’s output averaged $5.93 This is one of the most striking characteristics of the global watch industry. The total value of all Chinese exports (more than 80 percent of the world’s total units) was less than Rolex’s turnover and half the Swatch Group’s revenue.94 (SMH was renamed the Swatch Group in 1998 in recognition of Swatch’s contribution to reviving the company). In 2004, Switzerland controlled more than 40 percent of the global market measured in value, nearly 50 percent more than Hong Kong, its nearest competitor.95

The Swiss continued to dominate (and derive much of their profits from) the high- end, but such continuity was not inevitable. Landes argued that the shift to quartz technology meant little to the “great ‘name’ houses, whose reputation for quality and style and whose ability to confer prestige make cost considerations almost irrelevant.”96 That was not entirely true. Even though many of the prestigious “double-barreled names” like Jaeger-LeCoultre, Audemars Piguet and Vacheron Constantin that produced luxury watches for centuries continued to lead the high-end, the basis of their success changed and they were joined by newer watchmakers offering different value propositions. They created new products and the nature of their distribution evolved. Thompson credits the watchmaker Blancpain, and particularly its chief executive Jean-Claude Biver, for charting a new course for the industry: “Biver saw that there was an opportunity to position the mechanical watch as a limited-production, hand-crafted (hence expensive) luxury item.”97 In its marketing the company declared, “Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain. And there never will be.” Thompson suggested this was an impressive “feat of jujitsu.” “Suddenly the mechanicals' weaknesses (old-tech inaccuracy; labour-intensive, hence high, production costs; produced by outmoded, outmaneuvered, out-of-touch Swiss companies) became its strengths (old-world craftsmanship; created by artisans in accord with a 400-year-old traditions, to make rare expensive masterpieces.)”98

Even ne plus ultra manufacturers like Patek Philippe hedged their bets by converting a significant percentage of their production to quartz, what was more important was updating their marketing. Hank Edelman, president of Patek in the United States, said the critical juncture for his company was the decision to “unify our worldwide advertising and unify the message that we gave to the world about our brand” in 1984.99 The message, as conveyed by company chairman Philippe Stern, is that a Patek Philippe is “not really something to give you the time. It's more a piece of art, like a painting.”100 Like fine art, the value and desirability of fine watches was buttressed by a growing interest in watch collecting. Watchmakers sponsored watch auctions and created special editions for major watch sales to stimulate brand interest. Thompson argued “auctions were an early sign of the mechanical counter-revolution: some people were beginning to regard them as valuable pieces of art in contrast to the robotized, ‘untouched by human hands’ quartz watches.”101

Furthermore, the act of designing and producing mechanical watches changed fundamentally. The components that drove new high-end watches remained mechanical and assembly continued by hand, but the process was fundamentally different. According to Thompson “the revived mechanical technology differed from its pre-quartz-era predecessors. It was driven by a wave of high-mechanical innovation made possible by modern technology that brought unprecedented miniaturization and complication to mechanical movements. The result: new, more expensive, more exciting breakthroughs in mechanical watches and watchmaking, which has generated high consumer interest and sales.”102

These acts of entrepreneurship, hastened by the competitive challenge faced by Swiss watchmakers in the early 1980s, helped the industry recover and grow in new directions. The technological nature of the product is usually the focus when discussing the history of innovation. However, the Swiss experience illustrates that innovation in design, production, marketing and distribution can be more important in stimulating growth.

A conducive climate

High-end watchmakers benefited from a growing class of affluent customers who sought to consume beautiful “objects d’art”. The sociologist Thorstein Veblen famously asserted that individuals seek to signal their social position through visible displays of wealth, “In order to gain and to hold the esteem of men, wealth must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence”103 The only utility of products was to mark one’s position in the social hierarchy, either through “invidious comparison” as a way for a member of a higher class distinguishing himself from his lesser or “pecuniary emulation” when a lower class individual consumers conspicuously so that he will be thought a member of a higher class.

Culturally, the 1980s have been seen as an era of relentless materialism tied to the growth of free market economics. The market liberalization associated with Thatcher and Reagan and the “Greed is good” ethos witnessed its cultural expression in the popular satirical work of Tom Wolfe, Bret Easton Ellis, and in filmmaker Oliver Stone’s movie Wall Street. In Ellis’ Dostoyevskian portrayal of dehumanization amid hyper-materialism American Psycho, the main character Patrick Bateman checks his (or someone else’s) Rolex no fewer than 26 times.104 Popular media portrayals of luxury watch consumers inevitably feature high-flying investment bankers comparing Patek Philippe “Pagodas” and Rolex “Daytonas”: “these are people who have a certain intuitiveness; they know how much things cost. They ascertain what a guy's capability or monetary status is by looking at his watch. They know if he's a player. Or they think they know.”105 The “Veblen effect” is the supposed willingness of a consumer to pay a higher price for a functionally equivalent good as a signaling mechanism.106 Indeed the Economist argued “men flocked to the likes of Patek Philippe and Ebel, apparently because watches are the one sort of luxury good that has what marketers at Cartier smilingly describe as a ‘functional alibi.’”107

The growth globally of affluent individuals expanded the market for high-end watches. The 1980s witnessed growing wealth inequality in the United States, a trend that would continue (albeit later) in much of the rest of the industrialized world.108 The very wealthiest have seen their assets grow most drastically, but it is the next group down that is arguably far more economically influential and it was this group that buoyed the fortunes of the Swiss watch industry. Although watches like the Patek Philippe Calibre 89 that sold for $2.7 million in 1989 and customers like the Arab sheikh who reportedly bought his gold watches by the gross make the news, it is customers like Cecil Harvell, a 38 year old lawyer in Morehead City, North Carolina, whose wife bought him a $17,500 Patek Philippe that make up the majority of Swiss mechanical watch buyers.109 The New York Times reported Mr. Harvell liked the statement the watch made and “viewed the watch as a keepsake that could be passed down through the family.”

The Veblenian thesis fails to explain why it is mechanical Swiss watches in particular that kept hold of the market. The same cultural milieu that produced a wealth of popular discourse on the subject also incubated an abundance of academic scholarship on material culture. One of its most prominent thinkers, T.J. Jackson Lears, described a search for authenticity through consumption of handmade goods that seemed to lend a degree of permanence to an otherwise ephemeral modern world.110 The act of “jujitsu” whereby craft tradition and authenticity became important selling points is akin to Lears’ depiction of an omnipotent market that “transmogrifies” everything it touches into an agent of capitalism.111 Talented craftsmen in the mountains of Switzerland spending as much as a year assembling an individual watch contributed to the romance of the product. With his flair for the dramatic Hayek captured the sentiment (and selling point) of Swiss watches when he said, “We’re nice people from a small country. We have nice mountains and clear water.” He stressed the importance of selling brand messages, and a crucial component of his brands’ messages is Switzerland: “the Swiss have much more recognition as art producers, as producers of the mentality of Switzerland in the watches. People believe that our watches were better than any other watch even though the Japanese quartz were at least as good as ours.”112

While Seiko produced high-end mechanical watches under its Grand Seiko and Credor lines, it never successfully distributed these outside Japan. In 1981 it even purchased a bankrupt Swiss luxury brand called Jean Lasalle in the hope of entering the high-end market.113 In an industry where brand identity meant so much, a luxury Seiko was incongruous. Through its marketing, Seiko cultivated an image as a pioneer in high-technology, a brand message that did not sit comfortably with the hand-crafted, labour-intensive image necessary for selling limited quantities of very high-end watches. As the president of the watchmaker Movado Efraim Grinberg said, “You have to have a brand image and brand heritage and they didn’t have that…People buy watches for what they say about themselves. The Japanese have not been able to pull it off. You walk in wearing a Japanese watch, it doesn’t say something about you.”114

The growth of Swiss mechanical watch sales were part of the trend the business consultants Michael Silverstein and Neil Fiske called “trading up”.115 Customers are willing to spend more on quality products in categories they care about, while economizing on products that are less important to them. They want something qualitatively different, and this was what the mechanical watch provided. The authors suggested the “new luxury products” possessed artisan touches that evoke a level of quality, and satisfy customers by providing superior technical, functional, and emotional benefits. They had a strong tradition and “story”. It is easier for consumers to associate mechanical watches with the brand message of Switzerland. According to a UBS study, “brand Switzerland” is most evocative of “quality, tradition, and innovation,” and Swiss watchmakers have leveraged these perceptions in growing the market for qualitatively different watches.116

Unit production of mechanical watches increased more than 50 percent between 1990 and 2005 (2.2 million to 3.4 million units), while the value of such production grew nearly 200 percent (CHF 2,450 million to CHF 7,155 million) over the same period.117 The upscale Omega, whose recovery in the early 1980s was centered on the idea that the “electric watch is here to stay,” returned to producing predominantly mechanical watches by the early twenty-first century. In 2005, 65 percent of Omegas produced had mechanical movements, contributing considerably more in value terms.118 Typifying the transformation, Hayek, who made his name and a good part of his fortune on the back of Swatch (and is even known by the moniker Mr. Swatch), personally took control of the storied luxury watch house Breguet in 1999 and promised he would never make a quartz Breguet.119 Swatch, which once contributed around three-quarters of group profit, accounted for around 15 percent in 2005.120

The industry’s strategy changed. Quartz came to be seen as a mass market and “unemotional” technology. After scrambling to adopt the new technology to show they were not completely blind to market demand, Swiss watchmakers happily re-embraced their traditional technique when the market showed a predilection for nostalgically emotional products. As the erosion of the low and middle segments of the market continued, the Swiss sold more, and considerably more expensive, mechanical watches. Even as Hayek said, “you can buy a watch in my company for any price you want. If you are interested in a watch for $30 you will get it, if you are interested in a watch for $30 million you’ll get it also,” the majority of Swiss watchmakers have abandoned the former and are climbing toward the latter.121

A watch requires science and art and so does an industry

Through their marketing, Swiss watchmakers cultivated an image as the product of distinction, in many cases worth saving a lifetime to buy. There is a bit of Veblen’s notion of “pecuniary emulation” in their purchase, they are unquestionably a status symbol. The fine Swiss watch is a symbol that its wearer has “made it”, a characteristic reinforced by sophisticated worldwide marketing that stresses association with success, beauty, and lifelong enjoyment.

Material products have long held greater value to individuals than the sum of their basic utility. In a world where basic utility in products is assumed, the entrepreneur has dual roles. He must be “the powerful lever that in the long run expands output and brings down prices” by improving techniques of production and distribution, but he must also be the force that creates and steers demand.122 When Swiss watch entrepreneurs convinced affluent buyers that “A Patek Philippe doesn’t just tell you the time, it tells you something about yourself,” that is exactly what they accomplished.123

Historically, moving up-market when faced with a technological paradigm shift has been unsuccessful for many countries and many industries, simply postponing the decline as more versatile competitors consolidate their advantages throughout the market. The top of the range is not generally a large enough slice of the market to sustain the kinds of investments in production, research and development and distribution that are necessary for modern business success. The watch industry is something of a historical anomaly. Because of the shape of market demand a very small part of the market is exceptionally lucrative. Nevertheless, the Swiss did not survive the competitive threat posed by quartz and integrated mass production by ignoring the new technology, retreating into protectionism and resting on their historical superiority. Even as the products they sell retain the legacy of hundreds of years of craft tradition and utilize centuries old engineering, the way they are produced, marketed and distributed have been fundamentally reorganized in light of the quartz “invasion”. That process parlayed the industry’s historical strengths into new competitive advantages.

Schumpeter’s legacy reminds us that in a capitalist economy innovation cannot cease. If we accept Marshall’s claim that the entrepreneur is the fourth pillar of production, it is the entrepreneur’s job to arrange land, labour, and capital in such a way that production makes sense under prevailing economic conditions. The shape production takes depends in large part on factor conditions, as Broadberry correctly stressed, but it also depends on competition and demand conditions. As the case of the Swiss watch industry illustrates, sometimes it requires a brush with extinction to unlock entrepreneurial talent and alter prevailing constraints to make the necessary changes.

The Swiss position today is in no way inviolable. The basis of competition will continuously change as will the criteria on which consumers perceive value. Today, the Swiss benefit from a world where many relatively affluent customers choose to wear pricey mechanical objects on their wrist as a way of counting the passage of time and expressing something about themselves. Who is to say that they will make the same choice tomorrow?

The author with Swatch Group Founder and Chairman, Nicolas G. Hayek, Cap d’Antibes, France, 12 July 2006.

For reference to any of the footnotes above, see the attached original.

Congrats on the Acquired mention, very cool!